|

On duty in Aachen as Luftwaffenhelfer April 17th to September 12th 1944 (schw . z b V. 2 . / 5 1 4) by Gustave H. Roosen (updated 05. 01. / 2002) Preface: In 1943 the Germans started to conscript even young boys at the age of 15 and 16 as helpers into either the marine or the anti-aircraft ("Flak") forces. These boys were called "Marinehelfer" or "Luftwaffenhelfer" and were required to do the same full-time service as an ordinary soldier or sailor. A booklet "Mit 15 an die Kanonen" has already been published about the "Luftwaffenhelfer" in the city of Aachen. In this city at that time there were about 6 anti-aircraft batteries each consisting of 5 or 6 heavy 88mm guns. The designation "schw.zbV 2./514" refers to the 2nd battery in the 514th Group. The following war-related events, as experienced by a 16 year old Flakhelfer, are not intended to glorify any aspect of Hitler's Third Reich. (I am obliged to Mr. John Milloy, Kingston, Canada for translation of the original report from German into English. The author.)  On April 17th 1944, I and some other 16 year old grammar-school students from Monschau/Eifel reported for our military service in Aachen.

Our arrival was one week after a heavy air-raid on the city and we were posted to the battery at Vaalser Quartier/Vensky-Häus'chen. This battery was located right at the main road about 6 km distance from Vaals

in Holland and near the Belgium border, at a corner known as Dreiländereck, that is 'Three Lands Corner'.

On April 17th 1944, I and some other 16 year old grammar-school students from Monschau/Eifel reported for our military service in Aachen.

Our arrival was one week after a heavy air-raid on the city and we were posted to the battery at Vaalser Quartier/Vensky-Häus'chen. This battery was located right at the main road about 6 km distance from Vaals

in Holland and near the Belgium border, at a corner known as Dreiländereck, that is 'Three Lands Corner'.

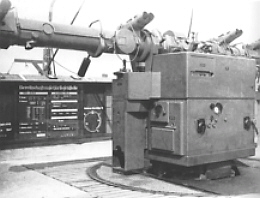

At this time I was a student in a type of high school known as "Alumnat", compar- able to a boarding school, although our accomodation was not in the actual school. There are no schools of this type today. The Alumnat, or "Crate" as we called it, is still standing. In the meantime it has been completely renovated, but until 1998 it was a decrepit relic and in danger of collapsing. Starting in 1943 our headmaster at the time, a Mr. B, called "Nero", who was both feared and admired, had also been ordered to report for duty to the anti-aircraft battery and starting at that time everything in the "Crate" was turned upside down. The law of the jungle prevailed. There was only supervision by the hour from the teachers, who could not in general do justice to their job in the prevailing chaos. It was hell! Scholastic achievement? Unfortunately not so! We arrived therefore on April 17th at the battery position and were received at the Reception Centre by the Battery Commander, Oberleutnant Kr. We were then issued our complete soldier's uniform and kit. Then we were assigned, according to the duty rota schedule-plan, to the guns, or the range-finding, or to communications. We were assigned as well as to the beginning of basic training and to the introduction of the equipment to which we had allocated. Some of us, including my friend Paul St., were assigned to the MALSI-appliance, a piece of equipment, used by the range-finding-staff.  Each of us also

had to spend two hours every day as observers - keeping a lookout for approaching aircraft. Our battery used 88mm AA guns of a type already employed in Africa.

Each gun stood on level ground on its carriage, surrounded by a baffle wall of approximately 2m in height. Since our position was situated at the

"Three-land-corner", we were beside the other batteries on the advanced post;but we were the firstof the batteries at the three international boundaries. The enemy-aircraft-warning post carried great responsibility.

If a vapour-trail was identified too late and the accompanying unidentified flying object that had caused the vapour-trail not identified, it could have nasty results not only for us but also for the

city of Aachen. Each of us also

had to spend two hours every day as observers - keeping a lookout for approaching aircraft. Our battery used 88mm AA guns of a type already employed in Africa.

Each gun stood on level ground on its carriage, surrounded by a baffle wall of approximately 2m in height. Since our position was situated at the

"Three-land-corner", we were beside the other batteries on the advanced post;but we were the firstof the batteries at the three international boundaries. The enemy-aircraft-warning post carried great responsibility.

If a vapour-trail was identified too late and the accompanying unidentified flying object that had caused the vapour-trail not identified, it could have nasty results not only for us but also for the

city of Aachen.Our battery commander was a wiry Austrian, a sharp, tough, unambigous, 150% ideologically fixed go-getter in his mid thirtees. During the hot days of that hot summer he placed a deck chair at the base of "B1" (the main-item of command equipment for observing and following flying targets) and sunned himself. While doing this he would continuously squint at the enemy-aircraft-warning post whether he was watching the horizon for vapour-trails or the edge of the forest for other targets. As an advanced battery, next to the border, we were mostly dependent on our own observations. It happened very often that we had to sound the alarm-bell in order to change

from "stand-by" to "ready-for-action" merely on the basis of a detected vapour-trail. The crew of the B1-range-finder quickly scrambled

and obtained the data from the twin-telescope and fed them into a 4-m-wide command unit, a type of an analog-computer (made by the German branch of

IBM - according to the logo on it) manned by a four-men-crew plus the chief (of the battery). "Target detected" was the verbal response of

the crew when the object, responsible for a vapour-trail, was identified and its direction, height, and speed of approach calculated.

Eyes, trained in aircraft-recognition, identified the type of approaching aircraft or group of aircraft. The data, giving the characteristic of the target, such as angle of altitude, speed and distance,

were electronically transmitted to the gun crew. The guns were then quickly directed according to this data. Whatever had been

spoken into the throat microphone was heard by the gun-commanders in their headphones. In the event of firebell not ringing, they pulled

on the gun's firing-cord on the keywords "Firebell" and "Fire!", thus triggering off the actual firing of the AA-shells.

This was followed by an interval of 5 seconds which was required for reloading the guns and so on. We were probably all happy to have escaped the dreary every-day-life at school and to emulate those elder students whom we had admired and envied when they were on leave, resplendent in their smart uniforms, from their "Home Flak" unit. No one wore the broad "HJ" arm band. We felt closer to the soldiers than the Hitler Youth, and were proud to wear the typical Luftwaffe belt and the buckle adorned with the eagle. Actually my friend Kurt H. came earlier to an anti aircraft unit: first to Jülich on a 20mm quadruple AA weapon as part of the ack-ack-protection for a train repair workshop and later, in February '44, to the Vaalser position in Aachen. He experienced the very heavy air-raid on Aachen on the night of April 11th, at the Easter holiday, and for him it was a bit too close for comfort. This nocturnal air raid was reported in all our newspapers as a "Terror attack". My friend Kurt told us of the following: "How proud I was at first to be allowed to defend the Fatherland. But that changed considerably to disillusionment after the attacks in April '44. The gun "Dora" in the battery received a direct hit and the entire gun crew was killed. Phosphorous had rained down on us and a stick of bombs had ripped the electric cables and the battery was out of action. On the following morning nine strips of canvas were laid out and the remains of our comrades who had died were collected and given to their parents for the purpose of burial at home. This horror scene happened one week before I arrived and consequently, we were very busy. The only time we sat was at the half-underground "MALSI" appliance while Kurt related everything in detail that happened at the "B1" site. He told us how during an air raid by a group of Liberator bombers he had seen, through the "B1" command optic equipment, the bomb-bay doors open and the bombs came hurtling down on us. "We had orders to shoot only at approaching targets (because of the short time fuse on the shells) and at planes which still had their bomb loads. Because of this we suddenly received the order to "change target to direction 12" and ten seconds later we heard "Full cover!". With a last quick look I saw the red carrots and green vegetables coming over me before it became dark from the debris that clattered down on us. We had unbelievable luck. The sticks of bombs just barely missed us, and only the radar screen was damaged...it was twisted into the shape of a figure "8". But there was a great bomb crater every 30 meters. Someone had counted all the craters within a radius of 500 meters and I believe the count was about 400...the most of them experienced since August 1944." There had been no talk about school lessons since July. With constantly being on stand-by and occupied with air raids, it was impossible for the teachers to teach lessons, particularly since in the direct vicinity there didn't exist any shelter for them in the event of an air raid alarm. By July we had received our school report cards and the marks included a danger bonus.

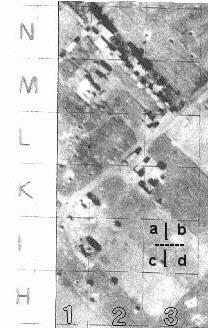

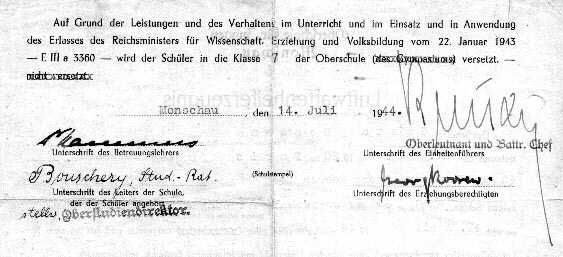

My earlier poor performance in grades had shown an abrupt improvement and my promotion to the next grade was also no longer in danger, indeed it was assured. The pain in-the-neck military drill didn't affect us very much. As a result of our membership in the HJ we had been well drilled. Those among us who had been involved in air-crew in the HJ had a good practical sense; therefore, the understanding of the technical equipment and all it's trappings that we came in contact with here, had quite a fascination for us. A number of basic training exercises and some unnecessary harassment naturally got on our nerves. Whenever anyone criticised us for smoking for example, we countered with the observation that if smoking is forbidden for us then also should the carrying of heavy boxes of ammunition. It may well have been July when the entire staff of the battery, including the battery commander and his 20-year-old adjutant, Lieutnant Kü. (also an Austrian) were sent to the front to relieve other battle-weary troops. Only the hated Corporal, exposed as a coward, remained with the battery as the action at the front really got underway. Now in exchange we received a battle-hardened crew, fresh from the front. They were fine fellows, and at that time we found them generous, casual, and easy to deal with. There was no drill, neither was there any ideological instructions nor disputes. The new battery chief sat himself on a stool at lunch in the canteen and entertained us on his accordian. The new way was indeed as different as day is from night. They were pals for us, really super pals. Service at the front had shaped these men. Instead of drill and twisted theories they had a whole new set of standards: practiced and proven strategies, based on experience, for surviving; comradeship towards each other and in which we also naturally, were included - and with it a significant enhancement in our status. The hated Corporal was put out of harm's way and henceforth never had an opportunity to harass anyone in any shape or form. The accomodation barracks, which I shared with others was fitted with some items I'd scrounged and brought from home: a wall mirror, window curtains, mirror lighting. And if one of the NCO's stepped into the room and received the required formal barrack-room announcement, then he would make some good-natured comment, look in the mirror, turn the light on and would probably be reminded of his own home and for a moment feel some nostalgia. Caustic comments, similar to "it's like a bloody brothel in here" were seldom heared and when they were, it was usually from the uncivilized types. As well, the ability to improvise was regarded as one of the important virtues. Since I imagined myself to be somewhat talented in technical matters, I built an electrical hot-plate out of big empty marinade-cans, and even built-in a multi-way switch - now the luxurious kitchen was ready for the evening fried potatoes, not to mention the home-fries at lunchtime. Leeks from the nearby field made a good substitute for the missing onions. Another great improvisor was a fellow who had been a moulder in civilian life. He was able to cast an "ack-ack"-medal from a silver-spoon, which for the time being were simply awarded but not yet actually given to the recepient, due to supply shortage. After a successful casting he had also been able to give it a black, glossy, finish. We had to suffer attacks by fast low-flying enemy fighter bombers; this strafing had in the meantime intensified and one of us, by the name of Kirsch, positioned on the old tower "Peltzerturm", as a forwarded observer was shot and killed by one of these planes. We were deeply shocked when we learned of his death. "At the same time" my friend Kurt reminded us, "even we were also affected by these low-flying attacks. We watched these low-flying fighter bombers circling around and ducked into corners whenever things became too hot. One such aircraft on a course straight for us in "B1" dropped something in front of us, which had the appearance of a 'block-buster' bomb. I saw the thing tumbling through the air and thought to myself, "that is it, Kurt, m'lad" and took full cover. However, since nothing happened, we daringly raised ourselves. There, leaning against the wall at an angle, lay a big jettisened camouflaged extra-fuel tank with it's nose almost inside our B1. At the end of August we had to dig fox-holes which were covered with a concrete lid and had an entrance which enabled quick entry. When necessary, we were supposed to seek shelter here. We didn't want to admit to ourselves that it would be necessary one day to use them, but this changed on September 11th when we received a direct hit from American artillery. Our cosy barrack went up in flames and we lost all our personal effects. They said that we ought to be withdrawn. We had come to feel very close to this crew; to us they had become close friends and we thought of them as genuine and reliable comrades and did not want to leave them alone to their fate. We wrote and begged for approval to remain, but the higher authority rejected our request. At night we were loaded onto a truck with dimmed lights and a load of catering items which were not officially registrated. We set off on a marked-out route (later to become an autobahn) in the direction of Cologne. It was a pitch-dark night and on the way, because of the shaded headlights and bad visibility conditions for the driver, we were involved in a collision. Nothing happened to us but some of the 'unregistered' goodies spilled out onto the highway. One could see nothing, but if one happened to push one's foot against something, it was likely a packet of pumpernickel, tubes of cheese or cigarettes - for us, welcome lost property! (Pumpernickel bread is a kind of dark bread which isn't perishable. Incidentally, later on, a long time after the war, when I tuned into BFN/BFBS and listened to the first DJ, I remember "pumpernickel": it was the nick-name of Chris Howland, who was very popular with all his listeners, soldiers and civilians alike). We finally arrived in Cologne and our tiny group gathered itself together in the cathedral (Kölner Dom) square. By a curious coincidence I met my grandfather here. There I was in battle dress, dirty, hungry-looking, with a carbine, ammunition pouches, steel helmet, knapsack, haversack and water-bottle, and there in the square by pure chance, was my grandfather. We were flabbergasted! His face registered unbelievably, a mixture of fear and shock. But there was neither the time nor the opportunity for an explanation, c'est la guerre! Our bedraggled little company of boy-soldiers moved on - discipline asserted itself and we marched away.  Former location: Vaalserquartier / Aachen-Southwest Former location: Vaalserquartier / Aachen-SouthwestAirphoto dd.12.09.44, late afternoon --> therefore shadows behind the objects <--- N-1 frm dwn-left to right-above = barracks of measuring- N-2 "c/d" still under consideration N-3 fresh craters from the day before (US-artillery) M-1/2 the B1 with Malsi set in the souterrain M-2 "a" the Radar set M-3 in eastern direction the canteen and, farer, a shelter L-1/2 fresh craters and fox-holes K-1 "a" fresh craters from the day before (US-artillery) K-1/2 supposed 20mm ack-ack gun-surrounding I-1/2 one of the 88mm AA gun-surrounding I-2 "a-b" fresh craters of bombs H-1 above fox-hole H-2 fresh craters of bombs Epilogue: The location of the former anti-aircraft battery on Vaalserstrasse has in the meantime become a row of terraced houses in a housing scheme and at a distance of about 1700 m, as the crow flies, diagonally opposite the famous ultra-modern shaped Aachen clinic. The first battery commander at that time of my experience with the battery, the "150%"-one, Oberleutnant Kr., survived the war. I saw him some years later, about 1949 or so, in a cafe in Innsbruck/Tyrol on the renowned Maria-Theresia-Strasse. He was performing as a stand-up violinist for the entertainment of the guests, who sat there enjoying themselves as they sipped their "Braunen" coffee and ate chocolate layer-cake. No one there appeared to have any idea of the violinist's past - except me, a passing tourist...

If you have further interest in subsequent happenings to this Luftwaffenhelfer-crew you might find the report, titled "Hamburg / Flaktower Wilhelmsburg" of some interest.

|

During a heavy raid each gun would fire about 700 shells per hour. Our guns had extremely

long barrels, with correspondingly greater range, and after about a 1000 shots there would be excessive wear on the rifling of the barrel. This wearing of

the rifling would diminish the accuracy of the firing. I must confess, that at times while conducting the firing I became a little excited. The result of

the rapid firing of the guns was that the barrels would almost started to glow. Our friend Ernst N., member of the gun crew, had an awful lot to do!

During a heavy raid each gun would fire about 700 shells per hour. Our guns had extremely

long barrels, with correspondingly greater range, and after about a 1000 shots there would be excessive wear on the rifling of the barrel. This wearing of

the rifling would diminish the accuracy of the firing. I must confess, that at times while conducting the firing I became a little excited. The result of

the rapid firing of the guns was that the barrels would almost started to glow. Our friend Ernst N., member of the gun crew, had an awful lot to do!

I have heard nothing further

from the surviving members of the crew, who, as front-line soldiers, had been relieved by the original battery crew, but who themselves finished

up being involved in the heavy defensive battle at Aachen against the attacking U.S.Forces. After heavy fighting, Aachen fell to U.S.Forces,

apparently of the VII.Corps, on October 21st - five weeks after our ordered nocturnal breakout.

I have heard nothing further

from the surviving members of the crew, who, as front-line soldiers, had been relieved by the original battery crew, but who themselves finished

up being involved in the heavy defensive battle at Aachen against the attacking U.S.Forces. After heavy fighting, Aachen fell to U.S.Forces,

apparently of the VII.Corps, on October 21st - five weeks after our ordered nocturnal breakout.